alisi Ross thought it was the right rental.

The 26-year-old Baltimore man liked the look and feel of the two-story rowhouse in the 1200 block of Ashburton St. It was convenient to his classes at Coppin State University. Best of all: the landlord, Waz Properties, allowed dogs.

Ross paid $2,100 to cover the security deposit and the first month.

But when he moved in with his pit bull, Nikolas, in October, he discovered he had made a mistake.

The electricity had been hooked up illegally, court records show. The gas had been turned off.

But his biggest problem was that city housing inspectors had deemed the property unfit for human habitation. Officials had withdrawn the permit that allowed the landlord to rent it.

It was the kind of case that Baltimore leaders had in mind 70 years ago when they created the nation’s first housing court. Appalled by the slum conditions spreading in the then-growing city, they envisioned a tribunal that would hold landlords accountable for violating newly enacted safety codes.

In time, state lawmakers added a new tool intended to compel property owners to address problems. With the approval of a judge, a tenant in a troubled property may withhold monthly rent payments until the landlord makes repairs. The tenant pays the money instead into an escrow account controlled by the court.

If the problems are resolved in a timely fashion, the judge may release the money to the landlord. If not, the judge may award some or all of the money back to the tenant.

The system was supposed to foster safer, cleaner, better housing in Baltimore.

But a yearlong investigation by The Baltimore Sun has found that it routinely works against tenants, while in many cases failing to hold landlords accountable when they don’t ensure minimum standards of habitability.

A first-of-its-kind computer analysis

In Ross’ case, for example, Baltimore District Judge Katie Murphy O’Hara declined to sanction Waz Properties for renting an uninhabitable property. Instead, she asked Ross why he moved into it in the first place, and then waited two months to file a complaint.

She ordered Waz to repay Ross just half of his security deposit — $525 — and none of his rent. Then she gave Ross two weeks to move out.

“I still haven’t gotten my $525,” Ross said this month. “What’s going to happen to the landlord? What type of repercussions is he going to get?”

Hundreds of city tenants turn to rent escrow court for help resolving disputes each year. Their complaints trigger a process: A city housing inspector visits the property, reviews the claims and reports back to the court. The judge may then open the escrow account.

But The Sun found:

-

Judges diverted rent payments into escrow accounts less than half as often as they could have, based on inspectors’ findings. Inspectors reported threats to life, health and safety in 1,427 cases, court records show, but judges established accounts in just 702 of them.

-

Even when accounts were established, judges returned most of the money to landlords when the cases ended. In cases in which inspectors found homes to be illegal or unfit for habitation, judges ultimately awarded 89 percent of the escrow money to the landlords.

-

Judges reduced or waived rent in just 344 cases, or 6 percent of all complaints.

-

The landlord that received the most complaints is also the largest landlord: The Housing Authority of Baltimore City. Tenants filed 145 complaints against the agency, which manages 9,134 units.

-

In court, the outcomes tenants encountered most often were delays and dismissals. When complaints did proceed, judges routinely gave landlords more than three times longer to make repairs than the 30 days the law deems “reasonable.”

-

Judges routinely require tenants to pay all back rent landlords say is due before their complaints are heard. They do not typically require the landlords to show that they provided a habitable home — the legal basis for charging rent.

-

Tenants are required to hire attorneys or law students to represent them in court, or else represent themselves. Landlords may be represented by agents who are not attorneys.

-

Judges rapidly accepted landlord allegations of unpaid rent that trigger the eviction process, the most serious penalty that tenants can face. Yet they seldom imposed one of the most serious penalties against landlords who violate their legal obligations to provide livable homes: cash damages. Court records show judges awarded damages to tenants in fewer than 20 cases — less than one half of 1 percent of all cases.

About this series

Sun Investigates team members Doug Donovan and Jean Marbella spent a year examining Baltimore’s court system for landlord-tenant disputes. They spent dozens of hours observing court proceedings and touring tenants’ homes, interviewed dozens of tenants, landlords, officials, and analysts, and reviewed thousands of pages of court filings and other documents. The Baltimore Sun’s work was supported by a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network.

From the racially discriminatory redlining and blockbusting practices of the mid-20th century to the more recent subprime mortgages targeting poor borrowers, Baltimore has long struggled with inequities in housing.

In a city where a majority of homes are rentals, local leaders set up the housing court to help transform a blighted landscape. But seven decades later, much of Baltimore’s housing remains unhealthy and hazardous. Researchers have labeled a third of the city’s 128,000 rental units substandard.

Those conditions have an impact beyond the properties themselves. They help fuel the public-health scourges of lead poisoning, asthma and homelessness that research shows perpetuates low test scores in schools, unstable neighborhoods and crime.

The judges and property management firms that mediate the contentious relationship between tenants and landlords say The Sun’s findings oversimplify the complex dynamics between low-income renters and the property owners who are trying to squeeze profits out of impoverished neighborhoods.

“There’s a lot of animosity between the parties,” said Mark F. Scurti, chief judge of the civil division of Baltimore District Court, which hears tenant-landlord disputes. “We work hard to make sure we always give a fair opportunity to landlords and tenants to come into court to address the issues that are raised.

“There’s always room for improvement.”

Corey Brown grew up in rental homes in Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods. Now he’s a landlord himself.

Brown describes the low-income rental marketplace as a complicated mix of good and bad players on both sides. Responsible landlords compete for business alongside slumlords who ignore serious hazards; reliable renters seek stable housing while “professional tenants” manipulate the system to avoid paying rent.

He expressed sympathy for low-income renters who struggle with unemployment or low-paying jobs, little education, addiction, bad credit and criminal records.

“The court system is tenant-friendly,” said Brown, the 37-year-old president of C. Brown Properties. “Although it’s a judge-by-judge situation. Some judges see we have professional tenants out there who know how to jerk the system.”

Advocates for tenants say The Sun’s findings and their own research demonstrate a judicial bias: Judges blame tenants for substandard living conditions, when it is the legal responsibility of landlords to provide habitable housing.

“It’s very discouraging,” said David A. Super, a professor of law at Georgetown University who has written extensively on landlord-tenant law.

Super said the Sun’s findings indicate the court is failing low-income tenants. In the decades since escrow laws first emerged, he said, outcomes favorable to landlords have become increasingly common nationwide.

“Landlords are not going to be deterred from letting their places run down,” he said. “And tenants have little incentive to go to court.”

The challenge is particularly great in Baltimore, because a disproportionate number of the city’s residents rent rather than own their homes. Nearly 53 percent of the city’s more than 297,000 homes are rentals, according to Census figures. Nationwide, rentals make up 36 percent of homes.

In the Census Bureau’s most recent American Housing Survey, in 2013, Baltimore’s renters had the unhappy distinction of receiving more court-ordered eviction notices per capita than any other city. More than 67,000 notices that year led to more than 6,600 evictions.

Last year, nearly 70,000 eviction notices led to nearly 7,500 evictions.

Each case is decided separately, on its own merits, Scurti said. He "would hope" that previous cases or a landlord’s reputation doesn’t "create a bias.

“I have to take each case as it comes before me," he said.

Landlords have experience and resources that tenants generally don’t.

Renters who are behind in rent can rarely afford attorneys. But state law limits their options: Tenants may be represented in court only by an attorney or an attorney-supervised law student. Without one or the other, tenants are left to fend for themselves.

Landlords generally arrive in court with a property manager or an agent who specializes in the process. Under the same state law, neither has to be an attorney to represent property managers in the court.

“There are some inequities there,” Scurti said.

Baltimore’s housing court meets in the District Court building on Fayette Street downtown.

The view from there is grim.

Judges hear of aging and unaffordable rentals, indifferent landlords, deadbeat tenants and a bureaucracy that’s struggling to bring substandard housing up to code.

Small dramas with big consequences play out. A tenant who can’t prove he paid his rent says he has been diagnosed with dementia. A lawyer attributes delays in fixing up a bank-owned property to “zombie-like” squatters who caused $100,000 in damage. A mother tells a judge that rats ate the tips off her baby’s bottles.

Judges have been hearing landlord-tenant disputes for centuries. For most of that time, they proceeded under the assumption that tenants were responsible for the conditions of homes they rented.

It wasn’t until the late 1960s that state courts began to recognize an emerging legal right: If landlords violate the legal obligation to provide livable homes, tenants could withhold rent.

Baltimore, with its long history of slums, was already well ahead of the nation on tenants’ rights.

In 1947, the city became the first in the United States to establish a housing court in which health and housing inspectors could hold landlords accountable for fixing problems.

Two decades later, the Maryland General Assembly established the state’s first rent escrow court in Baltimore. Tenants could now seek help for conditions that “constitute a menace to the health, safety, welfare and reasonable comfort of its citizens.”

Today, the court mainly hears two types of actions: Tenants seeking repairs or other fixes to problems, called rent escrow court, and landlords seeking unpaid rent or eviction — simply, rent court.

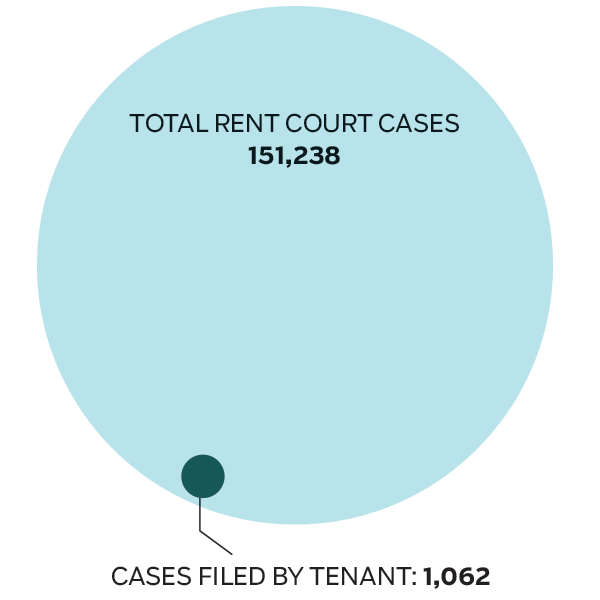

A rotating roster of 28 District Court judges hears nearly 152,000 cases each year. Some 150,000 are complaints by landlords that tenants failed to pay rent.

Tenants file some 850 complaints each year.

The Sun analyzed 5,500 of these tenant complaints and hundreds of criminal cases from 2010 through November 2016 in a database of state electronic court records maintained by the Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service.

The Sun filed a request with the Maryland Judiciary under the Public Information Act to obtain the case records directly from the state. The judiciary rejected the request. Officials said the request would require the agency to create a new public record from information that is already publicly available online.

The Housing Authority of Baltimore City, which owns and manages more than 9,000 public housing units, received the most complaints from tenants, according to The Sun’s analysis. Next were the large property management companies that handle hundreds or even thousands of rental units.

A spokeswoman for the city housing authority said the number of complaints represents a small fraction of the total number of public housing units. Federal regulations require annual inspections for public housing beyond those conducted for escrow cases.

“Given the age of the public housing inventory, significant maintenance problems can occur between inspections,” spokeswoman Tania Baker said. “As indicated by the data that was obtained, the number of these type of cases represent less than 1 percent of HABC’s current inventory.”

Reporters spent months sitting in hearings, visiting tenants in their homes, witnessing evictions, interviewing dozens of people and sifting through hundreds of court and inspection documents.

The Sun’s findings give weight to a complaint long expressed by tenants and their advocates: that the court works more as a collection agency for landlords than as a tool to correct housing problems.

Landlords typically receive favorable judgments in failure-to-pay-rent cases in mere minutes, allowing them to start the eviction process.

Surveys of tenants have shown that many renters are unaware of their right to challenge their landlords in court over unhealthy or dangerous living conditions.

When tenants do take action, they face a drawn-out process over multiple court appearances, with inspections, re-inspections and other delays.

Cases that involved serious code violations — meaning those that affect the life, health and safety of the tenants — took an average of 102 days from filing to resolution, The Sun found.

That’s “too long for the tenants,” Scurti said. But he added it “makes sense” given the legal requirements of formal notice to landlords, and the recurring problem of missed inspections.

The court is challenging for tenants, who in many cases take time off work and find child care to represent themselves in hearings that ultimately end in the landlords’ favor.

University of Baltimore professor Michele Cotton has studied housing court and proposed reforms.

“It’s up to tenants to assert their rights,” Cotton said. “But we’ve made it very difficult. It’s no wonder our housing stock in low-income communities is in such poor shape.”

Dionne Jones still doesn’t understand how rent court operates.

The 44-year-old federal employee turned to the court last year.

Initially, the five-bedroom house on Wentworth Road in West Baltimore seemed perfect for her family of five. But problems quickly emerged, Jones said in a complaint: There was no heat in the winter, no air conditioning in the summer, and mice year-round.

Jones, a case manager for Immigration and Customs Enforcement, continued paying the $1,895 monthly rent. She says she believed owner Peter Burke Jr. would fix the problems.

Neither Burke nor Bay Management, his professional property manager, responded to requests for comment.

By July, she says, she’d had enough. She filed a complaint.

“I’m beyond disgusted and disappointed,” she wrote in an email at the time. “I will NOT be paying rent to Bay Management until all of my concerns are addressed.”

But Jones, who represented herself, got nothing for her trouble.

A housing inspector testified at her first hearing that he found two code violations — both for mice — that were threats to life, health and safety. That’s the standard that allows a judge to open an escrow account.

The judge did not open an escrow account. Instead, he gave the landlord a month to repair problems that Jones had reported to him months earlier.

When a tenant tells a landlord of a problem, city law gives the landlord 30 days to make repairs. But judges routinely give landlords more time — 30 days from when the tenant files a complaint with the court.

Jones had been telling her landlord about the problems in her home for five months, according to records reviewed by The Sun. That would have enabled the judge to open an escrow account immediately, setting aside the rent money so that Jones could be compensated if the landlord failed to make repairs.

Support our investigative journalism

Become a Baltimore Sun subscriber today to support stories like this one. Start getting full access to our signature journalism for just $4.99 for 3 months.By the second hearing on Sept. 1, more than a month after the first, the violations remained unfixed. But a fed-up Jones had moved out a day earlier, without paying August rent.

Judge Devy Russell expressed confusion over how to proceed, an audio recording of the proceedings provided by the court makes clear.

Russell turned to the landlord’s representative for help.

That representative began to tell Russell that the home had been treated for rodents.

Jones broke in: “It was not —” she began. But Russell cut her off.

“Can you let her speak?” Russell told Jones. “I’ll give you an opportunity to speak. Please don’t interrupt her.”

Jones never got that opportunity. Instead, the judge asked the landlord to tell her how best to proceed. The landlord asked for a dismissal.

“Yeah, we’re just going to dismiss the escrow case,” Russell agreed immediately.

She further suggested that the landlord could pursue a civil action to collect rent for August. She did not determine whether the outstanding code violation entitled Jones to withhold August’s rent, or to the $11,370 in damages she had requested on her complaint petition.

“It was very discouraging,” Jones said.

A spokesman for the Maryland Judiciary said Jones did not “verbally” assert her request for damages, and said the judge could not do it for her.

Super, the Georgetown law professor, said tenants don’t have to raise an issue in court that they have already noted on the petition form in order to have it considered.

“That’s widely regarded as a bad thing, and was abandoned by most of the country in the 1930s,” he said. “And here we are, still using it.”

Nearly 60 percent of tenants who filed complaints of substandard conditions had their allegations verified in court by housing inspectors. At least a third of those code violations were noted in court records as threats to life, health and safety.

But the actual percentage of serious violations is likely higher, Cotton says and The Sun has confirmed through court records. The online case records used in the analysis do not always record all the violations inspectors find. In nearly 1,200 cases, the clerk reported no specific violations, even though judges opened escrow accounts.

Renters in Baltimore filed 5,511 complaints against landlords from 2010 through November 2016. Inspectors confirmed code violations that threatened life, health and safety in thousands of cases.

Representatives of the city’s largest landlords point to the number of units they manage and say the low rate of complaints show that their properties are well maintained. Advocates for tenants say most renters are unaware of the complaint process.

Baltimore rent court cases with life, health and safety code violations were extracted from the Maryland Judiciary Case Search by the Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service. The numbers of units were provided by the property managers.

Violations did not always lead to consequences for landlords.

Judges have three main legal tools to compel landlords to address problems promptly. They can divert rent payments away from landlords and into the escrow accounts, reduce or waive monthly rent payments to reflect the diminished value of unfit homes, or give rent money back to tenants. In addition, they can award damages if tenants request them, and hold landlords in contempt.

Judges opened escrow accounts in some 1,700 cases. That was only half of the cases in which inspectors confirmed code violations.

In those cases, judges ultimately released 63 percent of the $2.16 million put in escrow to the landlords.

In the 54 cases in which inspectors found homes to be “illegal” or “unfit” for habitation, landlords won 89 percent of the money.

Judges reduced rent to reflect the diminished value of hazardous homes in just 344 cases, or 6 percent of the total, the records show. They terminated leases in 11 percent of cases.

“Judges are not maximizing the incentive for landlords to make these repairs,” said Matt Hill, an attorney with the legal advocacy group Public Justice Center. “That’s a huge issue. If they did reduce the rent going into escrow, you’d see landlords more eagerly make repairs.”

Scurti said it is an “oversimplification” to judge the court’s rulings based on how money is disbursed from the escrow accounts.

Each case has its own unique set of facts, he said. The sides have different ideas of how much they each deserve. In some cases, landlords make partial repairs; in some cases, tenants put their own money into repairs.

The law gives judges broad authority to make whatever calculations they think best when determining how the money should be disbursed.

“You can’t look at it and say it favors landlords,” Scurti said. “It would be difficult to draw summary conclusions looking at the distribution of the funds.”

Landlords win because they enjoy the advantage of being “repeat players,” Hill said. Landlords and their agents know the judges and clerks, he said, and understand how the system works. Tenants, by contrast, arrive at hearings with little knowledge.

“They really are lost, and don’t know how to advocate,” Hill said.

The court system offers limited legal assistance to tenants. A video that explains the process plays on repeat on the second floor of the courthouse. The Public Justice Center maintains office hours in the building, and its attorneys announce their presence before eviction hearings begin.

The University of Maryland law school supports a landlord-tenant clinic that has provided legal help to about 15 clients each year. Most of the clients have been referred by staff at the University of Maryland Medical Center, who learn of unsafe or unhealthy homes when tenants seek medical help.

Deborah Weimer, the law professor who leads the clinic, said, “the system isn’t working the way it should.”

“There are no consequences for the landlords, which drives me crazy,” Weimer said. “And they’ll go out and rent [their houses] to someone else.”

Scurti said “the purpose of rent escrow is not to punish a landlord.”

“It’s to ensure compliance and to make sure the landlord keeps the property up to code,” he said.

Scurti said he is aware of the concerns of tenants and their advocates. He said he is working to improve training for judges and procedures for participants.

The Maryland judiciary is planning to launch pilot programs this year to improve tenants’ access to lawyers at the courthouse. Navigators will explain the escrow process to tenants, and the judiciary has hired a nonprofit to train lawyers to represent tenants on a pro bono basis.

“It’s an evolving process for me,” Scurti said. “I see that we are making great strides to improve it.”

One of the longest-lasting cases was filed by Angel Dow.

Tenant complaints analyzed by The Sun that involved threats to life, health and safety took an average of 102 days to resolve. Dow’s case dragged on for 20 months.

The landlord “endangered our health,” said Dow, 45, who works as a nurse’s aide at an assisted-living facility. “That’s why I didn’t drop the case.”

Dow, her husband and four children moved into a two-story rowhouse on Riggs Avenue in the Winchester neighborhood in March 2008. After the first year, she told The Sun, the problems began piling up: the back patio was deteriorating, the roof leaked, the basement flooded and became moldy.

She filed her complaint in August 2014, and a judge set up an escrow account. When several problems remained unrepaired in October, the judge gave Dow back the $1,700 she had paid, and waived the next month’s rent.

More hearings and inspections followed. Inspectors would note some violations being fixed, even as Dow said new problems emerged.

Dow said she was particularly concerned about peeling paint on the porch. The property lacked a certificate showing compliance with lead paint risk reduction standards.

Her concern grew in October 2015, when a granddaughter was born and moved in.

The Maryland Department of the Environment investigated, and filed its own complaint against the owner, Harry Mentzer, and the property manager, Corey Brown.

A contractor was sent to remediate the lead problem. But that wasn’t the end of it.

“The landlord failed to pay the certified lead contractor and ... he had initially stopped work at the property,” Dow’s lawyer, Syeetah Hampton-El of Green & Healthy Home Initiatives, wrote the Department of the Environment in August 2015.

Mentzer settled the case. He obtained a certificate in October 2015 and paid a penalty of $3,000. Brown was fined $25,000; as of this month, the Department of the Environment said, the fine has not been paid.

Dow complained about the lead abatement work. A Department of the Environment inspector found peeling and flaking paint in some areas of the house, documents show.

As the agency was working to resolve the problem, the Dows decided to move out. They left in April 2016, and the case was dismissed.

By then, the judge had waived rent multiple times. But there was still $3,400 in the escrow account. Dow was awarded the entire amount.

Brown said he was not the official property manager and that he was helping Mentzer obtain his lead certificate. He characterized Dow as a “professional tenant” who abused the process by filing over and over despite the good-faith efforts of Mentzer to make repairs. Mentzer declined to comment on the case.

Hampton-El said rent escrow court provides a venue for resolving disputes — “But you need everyone to participate.”

“We have an effective process here,” she said. “At the end of the day, it can only work if everyone is on board.”

It helped that Dow had an attorney.

Tia Hicks did not.

Tia Hicks complained to rent escrow court last year.

A city housing inspector found 13 violations in the rowhouse in the 2700 block of The Alameda where Hicks, 29, lived with her husband and her three children. Three of the violations were considered to be serious: a defective front porch, crumbling back steps and an upstairs pipe leaking into the kitchen ceiling.

The inspector also noted, with photos, rodent holes in the basement. The house is wedged between two vacant buildings; a Sun reporter observed a rat scurrying from one yard to the next.

Hicks’ complaint was dismissed, for one of the most common reasons: she refused to pay full rent for a property with multiple, proven violations.

Judges routinely require tenants to pay all back rent that landlords claim is due before they will hear the complaint. If the tenants don’t pay, the case is dismissed.

Tenant advocates have said this this amounts to a “pay-to-play” system that violates the due process rights of the tenants.

The law allows judges to reduce or waive rent in cases when code violations have diminished the value of a home. But judges typically don’t hear evidence to support such claims.

“It’s unconstitutional to basically require the tenant to pay an amount that hasn’t been shown to be due and owing to raise their defense,” said Zafar Shah, an attorney with the Public Justice Center. “They have to be able to raise a defense without paying to have their defense heard.”

Hicks filed a complaint against landlord Bolanle Famakin last summer. When Hicks failed to deposit her $1,200 monthly rent into the court account — she said she didn’t have the money — a judge dismissed the action.

Hicks showed the home to a Sun reporter.

“We have the mice getting in our bed,” she said. Traps were tucked into every corner of her bedroom, where her youngest watched TV in front of a space heater — because, Hicks said, the boiler was broken.

A month after the complaint was dismissed, more problems arose. Hicks filed a new complaint.

At a November hearing, the inspector reported the same 13 problems as before, and three new ones, including mold.

Judge Jennifer Etheridge gave Hicks seven days to pay three months’ rent — $3,600 — that the landlord said was due.

“If you don’t fund the [escrow] account, the case will be dismissed,” the judge said.

Hicks countered that it was not fair to charge the full amount of rent for a home with so many violations.

Landlords often say they cannot afford to repair serious violations if tenants do not pay rent. Advocates for tenants point out that the law requires landlords to guarantee their homes are habitable before they rent them.

If violations are confirmed by inspectors, they say, judges should consider reducing the rent before dismissing a case.

When tenants decide on their own to stop paying, judges often side with landlords.

“If she had September and October rent,” Etheridge said, “she would have the $1,000 to fix those problems.”

Hicks didn’t deposit the $3,600. She said she didn’t have it. Etheridge dismissed the case.

Five days later, Hicks called 311 about the lack of heat. She sent her two older children to stay with relatives to escape the cold. A city inspector issued another citation against Famakin for insufficient heat.

Famakin dispatched repairmen to fix the problems, including the heat. But Hicks was already making plans to move.

“That’s the only outcome for us,” she said. “To pack up our stuff and leave.”

Back in court in December, Famakin’s request to start the eviction process was approved in a few minutes. Hicks did not show up — a common occurrence among tenants.

The landlord said she had little sympathy for Hicks, the third tenant she evicted in the past five years. They lived free in her property for three months, she said.

“She is gaming the system,” Famakin said. “I can’t wait to get them out of there.”

Small landlords such as Famakin are the most common property owners in the city. Two or three months without rent can affect their ability to pay off their mortgages, forcing them into foreclosure and putting them out of a business. Landlords in low-income neighborhoods say such outcomes further imperil an already low supply of affordable homes.

Famakin does not employ a property manager. She drives in from Gaithersburg to deal with tenants in a house in which she has invested $80,000 since 2006.

“They were causing me to spend money that I didn’t have to,” she said.

Landlord Moses Fadiran said he’s had tenants fall behind in rent, and then file complaints.

Then they string out the process, Fadiran said, and exaggerate the severity of the problems.

He faulted the city for letting some blocks deteriorate, saying vacant houses adjacent to his properties can cause the water leaks and other problems that tenants complain about.

“You have next door, the roof caving in, you do the best you can,” he said. “Some have no roof, and a lot of rainwater gets into your basement.”

The city has taken Fadiran to court at least six times in recent years over alleged housing code violations. State environmental officials have cited him for lead paint violations.

Fadiran continues to rent properties across Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods.

In 2014, the city asked a judge to fine Fadiran $500 a day until he took care of a rodent infestation and other violations at a property in the 2400 block of Callow Ave. The case was dismissed, but by then, tenants living in two apartments in the building had filed escrow cases against Fadiran as well.

“Our apt is infested with rats and landlord did not tell us before move in,” one couple said in a petition for escrow. “Rats/mouse tear the toilet paper up and more.”

A housing inspector found 20 code violations, including 12 threats to life, health and safety. The couple moved out, and a judge closed the case and forgave any past rent.

In another case, at a house in the 3400 block of Paton Ave., court documents show a housing inspector found 30 violations, 24 considered threats to life, health and safety.

Robin Budd rented the home in 2014. She can still tick off its many problems, from water and gas leaks to rodents to a bad gate and fencing that failed to keep the neighborhood pit bulls out, that led to an escrow action.

Even repairs tended to beget more problems, she said.

“We had a gas leak from the stove,” Budd said. “He took the stove out and brought a new one in, and that one had a mouse running out of it,” she said. “And there was still a gas leak.”

The leak eventually was traced to a pipeline and repaired, she said. It took close to half a year to resolve the problems. A judge forgave one month’s rent, and split the five months’ rent paid into escrow. Landlord and tenant each received $2,125.

“I don’t think he shouldn’t have got [anything],” Budd said.

The Maryland Department of the Environment cited Fadiran in February for failing to get certificates showing the Paton Avenue house and another rental in the 2200 block of Orem Avenue were tested and treated to reduce lead paint risks. The agency fined him $45,000. The case has not yet been resolved.

State environmental officials had cited Fadiran in 2008 and again in 2011 for lead paint violations. Both were settled. Fadiran paid penalties of $3,000 and $1,000.

Fadiran denied that his properties were particularly problematic.

“I’m not saying I’m the best landlord. ‘Can I live in this house?’” he said he asks himself. “If the answer is no, I will not rent it out.”

Super says judges have steadily shifted the blame for living conditions away from landlords and onto tenants — a phenomenon he called “judicial moralizing.”

He said judges seldom take the time to determine whether property owners are violating their legal obligations to provide habitable homes before leasing to tenants.

“There is way too much informality,” Super said. “The judges should be required to make formal findings rather than lecture people from the bench.”

Super says judges can and should employ the legal concept of “implied warranty of habitability,” a guarantee that the house is livable. Put simply: If leases oblige tenants to pay rent, they also oblige landlords to provide livable homes. It they don’t, tenants are justified in withholding rent.

The concept began to emerge in state court decisions in the late 1960s that gave tenants recourse when landlords failed to make repairs and prohibited retaliatory evictions.

“These measures, eventually adopted in almost every state, seemed to reverse the landlord’s historical dominance of the landlord-tenant relationship,” Super wrote in a research paper.

But nearly 50 years later, he and others say, housing courts have become less rigorous about following standard procedures of evidence.

That was Cotton’s conclusion after analyzing 59 complaints selected at random from across the city. In each one, she said, the “findings of fact” space on court forms were blank.

The Sun found similar results sitting in court and reviewing transcripts and records of dozens of cases.

The Maryland Judiciary has approved new instructions for judges to ensure consistency. They are “in the process of being introduced across the state,” a court spokesman said.

Tenants have the right to ask judges to consider awarding them cash damages for a landlord’s violation of the warranty of habitability. The request can be made on the same form tenants use to file their rent escrow complaints.

But judges, landlords and tenant advocates all agree that the language on the form is clear only to people who know the law.

The document offers several boxes tenants may check to request certain rulings from the court. They include requesting that the judge correct the conditions at the house, reduce the rent, establish the escrow account, terminate the lease and dismiss a landlord’s eviction filing, if one exists.

The last box is not so plainly written: “The Tenant requests the Court to order that damages be awarded for breach of the covenant of quiet enjoyment or warranty of habitability in the amount of __.”

A committee of the Maryland Judiciary has been working since last year on a proposal to make the language on the form more clear.

Even when tenants know enough to make that request for cash damages, judges often do not address the matter in court. The Sun’s analysis of court records show that cash damages came up in just 26 cases — less than one-half of 1 percent of complaints — and were awarded in fewer than 20.

Anthony Johnson rented a rowhouse in the 3700 block of Gelston Drive last February for $950 a month. He didn’t know that city inspectors had deemed the home “unfit for human habitation.” The property did not have a city occupancy permit, and would receive its lead paint certification six months late — after Johnson moved in.

The city had ordered the property owner, Waz Properties, to board up the home, rehabilitate it or tear it down.

Instead, Waz put it up for rent.

Johnson learned of the citation when a housing official placed a “vacate” order on the property.

Johnson and Waz filed dueling complaints.

Johnson said the property had a “roof leak, basement door not opening, mold, possibility of lead.”

Waz said Johnson owed $2,849 in back rent for three months.

Johnson asked the court to terminate the lease and order Waz to pay him $10,500 for violating the warranty of habitability by renting the property for the 10 months he lived there.

Judge Etheridge vacillated over what to do, a recording of the hearing indicates.

She began to order Johnson to pay some amount, and said she would terminate the lease.

Then Waz’s representative, Sal Catalfano, who handles hundreds of cases for landlords each year, contested the allegation the property was uninhabitable.

An inspector told the judge the house lacked a proper permit and had been declared vacant. Catalfano blamed bureaucratic red tape.

The judge then began to order Johnson to pay $950 for one month’s rent and said she was going to dismiss Waz’s claim for the other two. Catalfano protested.

The judge ordered Catalfano and Johnson to try to negotiate a settlement in the hallway. When they could not, the judge began again to consider how much Johnson should pay.

“It looks like you’ve been behind for quite a while,” she said.

Johnson disputed Waz’s total. Then he asked a question that no one else had asked that day.

“How can they be renting the house if it’s supposed to be vacant?”

Etheridge paused, and then replied with a comment that Johnson considered odd, given that he was representing himself.

“Sir, today was your trial date,” the judge said. “If you wanted to have an attorney here you could have had an attorney present to ask those questions.

“You don’t get to live rent-free, which you’ve been doing for a couple months now. Right?”

Not right, advocates for tenants say. Under the law, Johnson’s request for $10,500 damages entitled him to make a case for being reimbursed for having paid rent at an uninhabitable home.

Johnson had checked the box on his complaint form to request damages. But he didn’t raise the request in court, and Etheridge didn’t consider it. She terminated the lease, dismissed the case and gave Johnson 11 days to move.

“You don’t have a lot of time to get out, sir,” she said. “You haven’t paid for quite a while. You can take that money and move.”

Requests for comment from Etheridge were returned by court spokesman Kevin Kane.

“The fact that a box was checked saying that relief was sought as to the Warranty of Habitability or covenant of quiet enjoyment is not the same as offering proof at trial,” Kane wrote in an email. “A judge must remain neutral and cannot raise issues on his or her own.”

He said the judge waived all of Johnson’s allegedly unpaid back rent — $4,790.

Johnson left town for a week to work in Pennsylvania. When he returned a day before the deadline to move, he says all of his electronics were missing and his two dogs had been impounded.

He climbed through a window to retrieve work clothes and some of his pregnant girlfriend’s possessions.

“We’re out of a whole household of things,” Johnson said. “We have a baby on the way.

“It seems like the judges and lawyers are all on the landlords’ side.”

Waz — which owns and operates properties under several corporate entities — is controlled by brothers Isaac and Benjamin Ouazana. It is among the 10 city landlords that The Sun identified as having the most tenant complaints.

The company and its affiliates own more than 100 units in about 80 properties, according to a city database of registration records obtained by The Sun through a Public Information Act request. Since 2015, tenants have filed 32 escrow actions against the company.

City inspectors issued 111 violations against properties owned by the brothers’ companies from 2010 to mid-2016. And the city’s housing prosecutors are pursuing two actions against them for nuisance properties.

Maryland’s Department of the Environment has assessed two fines — one for $27,500 and another for $22,000 — against Waz for maintaining properties out of compliance with lead laws, records show. Their failure to comply at both properties, according to the complaint, “created a potential danger to human health.”

Scurti took the rare step of holding Waz in contempt for failing to make repairs in a timely fashion in several cases.

Benjamin Ouazana said the company believes its properties are properly permitted when it rents them, but has sometimes been mistaken.

“We didn’t know,” he said. “Sometimes you buy a property and don’t know it doesn’t have a occupancy permit.”

Landlords have their own complaints. They say the process of evicting problem tenants is taking increasingly longer, and is costly for small mom-and-pop landlords.

Large landlords and property managers say small investors get in over their heads in a market they do not understand.

“It’s a very unfriendly climate for landlords in Baltimore,” said Keith French, an executive at Blue Star Property Management. “You have professional tenants who know how not to pay the rent just like you have slumlords. They come in and pay the first month and security. Then they stop paying, and we can’t get them out for three to six months.”

Ben Frederick III, a property manager, owner and broker in Baltimore for three decades, said such tenants force unsophisticated landlords out of the market and help drive the vacancy crisis the city faces today.

“Evicting people is not what I want to do,” he said. “It’s the worst thing to have to do. It’s horrible. But I’m not social services. It’s a business.”

Pat Mooney, a manager for property management firm Dunne Wright, said the process works better in Baltimore than in other Maryland jurisdictions because city judges rely on inspectors to provide objective findings.

His company, which manages about 700 properties, has faced dozens of escrow complaints.

“The judges are very fair,” Mooney said. “They understand what we’re dealing with.”

Michele Loving, 45, was one of the tenants with whom Mooney interacted. She works as a teacher’s aide in the Baltimore public schools, but worries about layoffs. She also works nights at a CVS in Severna Park and drives an Uber car that she leases from the ride-sharing company for about $145 per week.

Loving rented a Dunne Wright apartment with her husband in the 800 block of Jack St. in South Baltimore. In October, the ceiling in the dining room fell in, and the couple found bedbugs.

She filed a complaint in October. A judge set up an escrow account, and Loving paid in $1,260 for October and November.

Then she missed her third payment, and the case was dismissed.

The repairs were completed in November. Loving and Dunne Wright both received $630. Mooney called it fair, but Loving said it was unacceptable.

“We are leaving,” she said. “We are not paying anything else other than the water bill.”

She and her husband now pay $500 to rent a room on West Franklin Street.

Patrice Rooks and her four children moved into a West Baltimore rowhouse in the 4200 block of Flowerton Road in October. She had just earned a degree that would enable her to work as a licensed practical nurse.

She was thrilled: New career. New home. New life.

As it turned out, she said, the house “was the worst mistake of my life.”

She paid $1,200 a month for a house that immediately began to fall apart around her. Holes in the roof, ceilings and walls. Water damage. Mold. Lead paint. And, worst of all, rats.

“The rats ate away at the rubber on my baby’s bottles,” she testified before Scurti.

She called 311, and a city inspector found 20 code violations — 13 of them threats to life, health or safety. She filed a complaint against Waz in January.

Waz, meanwhile, had filed a failure-to-pay-rent action against her for a $4,500 water bill. Rooks said the bill was the landlord’s responsibility.

The cases were consolidated. At the Valentine’s Day hearing, no love was lost in Scurti’s courtroom.

Scurti grilled Waz’s representative, Nathaniel Arnson, about why problems reported in September were being addressed just prior to a court hearing months later.

“That’s outrageous,” said Scurti. He said he had “never” seen so many violations at one property in his three years on the bench.

The judge was also suspicious of the lead certificate number listed in the company’s failure-to-pay-rent complaint: 111111.

“I’ve never seen a lead certificate with six ones,” Scurti said.

Arnson had no records and no answers. He borrowed a pen and paper from a court clerk to take notes on Scurti’s demands: Complete all repairs in 10 days, take no action to evict Rooks and produce the lead certificate with “111111.”

“You have 24 hours,” Scurti said. “This woman has been living in a nightmare.”

He scheduled a follow-up hearing for the next day. He knew he would be in the courtroom.

“I’m keeping this case,” he said.

Scurti then gave Arnson a chance to speak.

“She moved out because of the rat issue — which I get ...” he began.

Scurti interrupted.

“There are 20 violations, 13 are threats to life, health and safety,” he said. “Don’t stand there and tell me she moved out because of the rats. She’s been very kind, very patient.”

Arnson returned the next day with a lead certificate. It did not contain the 111111 number that the judge had questioned.

The state has levied a $22,000 fine against Waz for failing to properly certify lead abatement at the address.

A day after the hearing, Rooks said, she went home from her job with her four children to find the doors padlocked. Because the windows do not lock, she was able to climb in and hoist her children in one by one.

Rooks appeared at the next hearing dressed in blue medical scrubs. She had left her new job at Greater Baltimore Medical Center on her first day to get to court.

She was the only party to appear. Instead of terminating the lease, Scurti decided to schedule another hearing. That would give Rooks time to save money to move, and prevent Waz from evicting her.

He then issued an order that is the first step toward holding Waz in contempt of his repair orders.

“Thank you, Judge,” Rooks said. “I just want this nightmare to end.”

Hampton-El, the Green & Healthy Homes Initiative attorney, understands what her clients face.

When she was a child in Wicomico County, her family was evicted once, their belongings dumped outside of the house where they rented the bottom floor. What she remembers most of the day is the rain — and the humiliation.

“My stuff is getting wet, and the adults were discussing things, and we had no place to go,” Hampton-El said. “We went to a shelter, and I’m in school, and it’s embarrassing.”

What she took from the experience — other than, “come heck or high water,” she would never get behind in her own rent — was how fraught housing disputes are. By the time a case lands in court, emotions are running high and it can be hard to get a resolution.

“No one’s talking to each other,” Hampton-El said. “Maybe the landlord has waited until the last day to make a repair, and then the work is shoddy. Or the tenant is so frustrated with the workers, so they stop allowing access to the house.”

Jesse Buckner’s case against Lanvale Towers apartments last year grew increasingly bitter as it went on.

Buckner, 66, receives Section 8 housing assistance and disability payments. Rent at the apartment at 1300 E. Lanvale St. came to $246 per month.

Buckner said he began complaining about bedbugs, rodents and other problems early in the year.

Owen Jarvis, an attorney with St. Ambrose Housing Aid Center, wrote a letter about the problems to Lanvale’s management in March. He filed a complaint for Buckner the next month.

A housing inspector told the court that she had found bedbugs in the apartment, but because maintenance workers refused to enter it to move the refrigerator, she couldn’t confirm Buckner’s complaint of a rodent hole behind the refrigerator.

Judge Kent J. Boles Jr. waived the rent for April and opened an escrow account.

Court documents show that an exterminator treated the apartment for bedbugs from June to September. A housing inspector told the court in July that all violations had been repaired, but Buckner said the apartment was still infested.

A representative for the landlord said Buckner was told he had to get rid of his mattress and other belongings but hadn’t.

Then Buckner missed several inspections. In August, Lanvale filed a breach of lease case to evict him. The company, which has not returned calls for comment, told the court Buckner had failed to recertify his Section 8 subsidy, as is required annually.

Buckner agreed to move out, but asked to stay until Nov. 7.

In September, the itching from the bedbugs had gotten so bad, Buckner said, he went to the emergency room at Mercy Medical Center. He asked to see a psychiatrist, he said, because he wanted to kill himself.

Discharge papers show the doctor prescribed hydrocortisone for the bedbug bites.

The following month, Judge Nicole Pastore Klein dismissed his case, and asked both sides to go into the hallway to see if they could agree on how to divide the $1,476 Buckner had paid into the court account over the past six months.

An attorney for Lanvale said there would be no agreement, given that Buckner kept missing inspection dates. Both sides made their pitch for why they should get the entire amount.

Jarvis said the bedbug problems began early in the year, and Buckner had to live with the insects for months.

Lanvale’s attorney said Buckner hadn’t cooperated by discarding his mattress or showing up for the inspections.

Because an inspector said all violations were abated in July, Klein decided to award the landlord the last three months of rent — $738. She gave May’s rent to Buckner, saying there were no treatment records entered for that month. She then split June and July’s rent, one month to each side.

Buckner received $492. Lanvale received $984.

And so, on Nov. 7, a scene that’s familiar in some parts of the city played out on Lanvale Street.

“Is he being put out?” a bystander asked in a whisper.

Buckner hired several men to help him move out. But he made the mistake, he would later grumble, of paying them in advance. They didn’t show up.

He paid another man $10 to help him haul stereo speakers, bags of clothes, a giant jug of detergent and other belongings into his old Chevy Blazer. They crammed the stuff inside, or stacked it on the roof.

Then, like an urban Joad, he drove slowly several blocks to his new place.

It is a rooming house on Wolfe Street, where the next four rowhouses to the south are boarded-up vacants. Across the street, you can see straight through the shell of a building.

Now he’s paying $450 for a single room — almost twice his rent at Lanvale Towers.

Legislation sponsored last year by then-state Sen. Catherine E. Pugh brought landlords, tenant advocates and judges together in a work group to discuss ways to improve rent court in Baltimore and across Maryland. After contentious negotiations, the group came to a consensus around several ideas and devised legislation. Their bill, which would have given tenants more rights to defend against eviction proceedings, was introduced in the Maryland General Assembly this year by Del. Samuel Rosenberg. It passed the House of Delegates but died in the Senate’s judicial proceedings committee.

But other solutions are in the works.

Train Landlords: The Maryland Multi-Housing Association has developed a best-practices curriculum for a “landlord academy” where judges could send problematic property owners. Status: Under Study.

Improve communication among judges: The Maryland Judiciary has devised a new checklist-style form for judges to provide a consistent record as judges rotate on and off individual cases. A new rent court instruction manual, or “bench book,” is also being considered. Status: Forms have been approved.

Deploy More Lawyers: Most tenants do not have an attorney when they go up against landlords in court. More legal representation could result in fewer evictions and better housing conditions.Status: A pro bono pilot program is set to start in May.

Deploy More Non-Lawyers: State law allows landlords to be represented in rent court proceedings by specialist agents who are not lawyers, while prohibiting tenants from the same representation. Rosenberg said the “disparity” should be fixed. Status: Not under consideration

Educate Tenants: The Baltimore District Court plans to try out a navigator program to provide specialists in landlord-tenant law to help renters understand their visits to the courthouse. Status: A pilot program is set to start in the Fall.

Eliminate Legalese: The Maryland Judiciary is considering a new tenant complaint form written in plain language to help renters who are alleging unsafe living conditions better understand all of their rights. Status: Under study.

Expand Inspections: The city performs routine annual inspections only of apartment buildings with three or more units — about 6,000 each year. That leaves tens of thousands of one- and two-unit rentals that go without inspections unless tenants complain. The Public Justice Center has called for expanded licensing as in other jurisdictions. Status: Not under consideration.

Contact Doug Donovan at ddonovan@baltsun.com

Contact Jean Marbella at jean.marbella@baltsun.com

The Baltimore Sun, supported by a grant from Solutions Journalism Network, reviewed state electronic court records of more than 5,500 rent court complaints filed by Baltimore tenants and hundreds of criminal cases from 2010 through November 2016. The information was extracted from the public Maryland Judiciary Case Search website and formulated into a searchable database by the Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service. (The Sun filed a request with the Maryland Judiciary under the Public Information Act to obtain the case records directly from the state, but the agency rejected the request.) Sun reporters performed checks to verify that the cases in the Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service matched those in the public database. Sun reporters worked with freelance developer Emanwel Turnbull, an attorney who has used the Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service database to conduct research, to identify outcomes and trends. They then pulled original case files from court records and the public database. Incomplete and incorrect entries by court data clerks may have resulted in tallies that do not reflect the full extent of court actions. The Sun also analyzed housing citation data from the Baltimore Environmental Control Board, city rental registration and licensing databases, and lead paint certification records from the Maryland Department of the Environment.

Leave a comment